20. oktober 2023 nyhet

This text is based on the article by Merkel and Strøm about what happens with young guillemots when they leave the cliff and swim out to sea with their fathers.

By Benjamin Merkel (Akvaplan-niva)

In seabirds, we can observe a wide variety of parental care strategies, with young of some species leaving the nest shortly after hatching, while others stay in the nest until they are adult size and able to fly. Three species of auk (common guillemot Uria aalge, Brünnich’s guillemot Uria lomvia and razorbill Alca torda) on the other hand have a unique third breeding strategy somewhere in between these. Their young leave the colony flightless, at only a quarter of adult body size, accompanied by the father and fledge (become independent) out at sea. This gives rise to the famous natural history phenomenon of tiny chicks leaping off steep cliffs and down sometimes hundreds of meters to swim out to sea with their fathers.

This second part of the breeding period out at sea was a mystery for the longest time as observational data are hard to come by in the open ocean. In our study (Merkel and Strøm 2023) we tested several hypotheses about this elusive period often referred to as swimming migration as father with their young have to swim to move as the young is still unable to fly. We equipped 34 chicks of common guillemots and Brünnich’s guillemots breeding at Bjørnøya, a major colony in the European Arctic, with satellite transmitters to track their swimming migration after they left the colony.

All young, presumably accompanied by their fathers, swam actively, rather than passively drifting away from the colony with currents, as previously hypothesised. They swam fastest during the first two days after leaving the colony. This coincided with the only time they actively crossed a major current and the time needed to leave the area of prey depletion around the colony. They otherwise took advantage of available currents, while still swimming actively during the remainder of their migration towards previously known autumn areas used by adult birds of the same species. These regions correspond to areas used by adult birds during their moulting period (when they renew their flight feathers), rather than being specific nursery areas only used by young (as previously hypothesised).

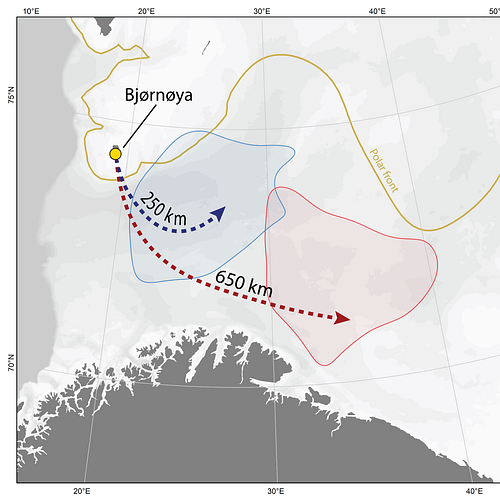

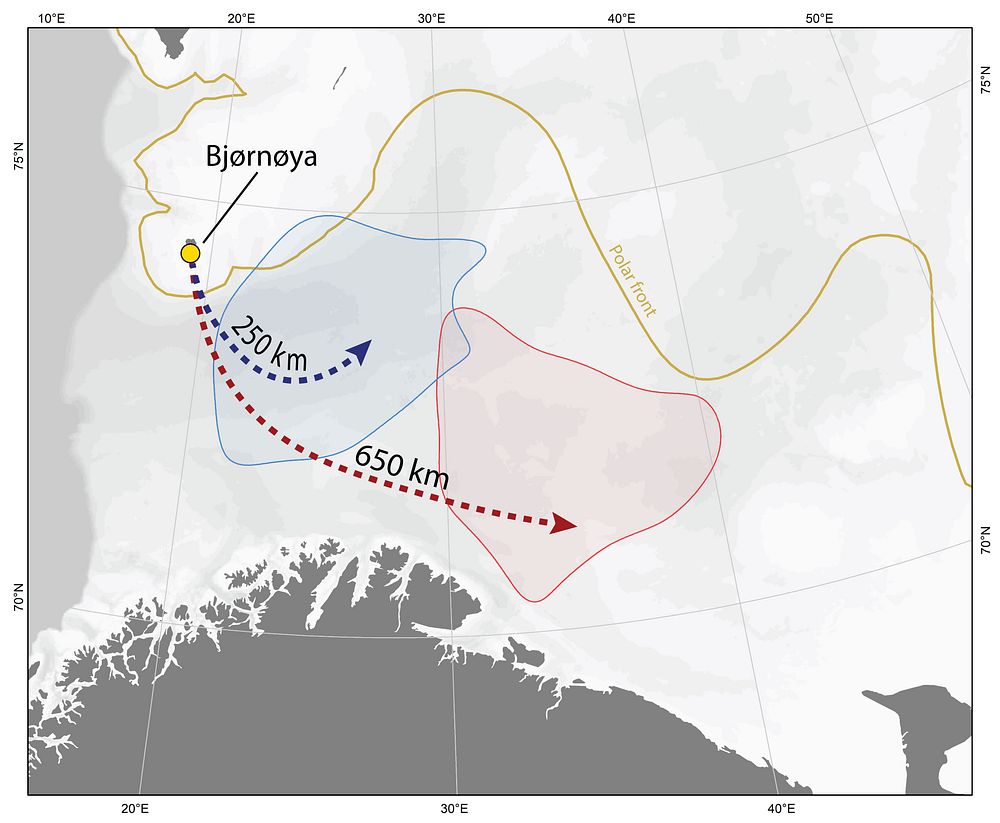

The Brünnich’s Guillemot’s moved about 250km away from the colony in around 14 days after their jump off the cliffs, whilst the Common Guillemots moved up to 650km in a swimming migration that took around 29 days. The young birds moved at a speed of around 1km per hour, and the Common Guillemots covered an average of 22km per day. Migration to these autumn areas took only a fraction of previously reported fledging periods out at sea (suggested in previous studies). This indicates that not only the swimming migration, but also the known adult autumn staging areas constitute in effect breeding areas.

Map illustrating the journey of the Brünnich’s (in blue) and common guillemots (in red), from the breeding colony on Bjørnøya (Map illustration by Benjamin Merkel/Akvaplan-niva).

This work has important implications for our understanding of population dynamics within the Alcini subfamily and the management of these species under multiple threats, while providing the foundation to investigate swimming migrations across their entire species range.

See BBC video of a Guillemot chick jumping from a cliff in Scotland that shows the incredible behaviour that leads into the swimming migration at the centre of the study by Merkel and Strøm.

This text has also been publised as blogpost in Journal of Avian Biology: http://www.avianbiology.org/blog/elusive-and-unique-swimming-migration-young-guillemots